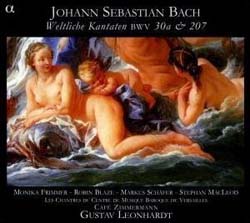

Johann Sebastian Bach, Weltliche Kantaten, BWV 30a and 207

Johann Sebastian Bach, Weltliche Kantaten, BWV 30a and 207

Monika Frimmer, Robin Blaze, Markus Schäfer, Stephan MacLeod

Les Chantres du centre de Musique Baroque de Versailles

Café Zimmerman, Gustav Leonhardt, Director

Alpha 118 (2007)

The historiography of J. S. Bach seems to wrestle less and less with competing images of the composer--chiefly the duel between the long iconic church musician and the worldly figure of court music and Zimmerman's Café--and increasingly to accept the complexity that makes both images apt. Admittedly, too, the opposition of sacred and secular imposes a rigid, modern divider where in the eighteenth century the walls would have been more permeable, if walls at all. No wonder that new images of Bach have seized the day, as in Christoph Wolff's monographic paradigm of Bach as the "learned musician." The recording at hand, a beautifully performed program of two of Bach's secular cantatas, might then serve less to buttress claims for the "secular Bach" than to revel in works written with characteristic artfulness and performed with stylish flair.

The recording Weltliche Kantaten appears in the "Ut pictura musica" series from Alpha Recordings. This series, an extensive one, dynamically pairs music and painting and invites the listener-viewer to savor the counterpoint. In this particular case, the visual component is the sensuously fleshy Le Triomphe de Vénus by François Boucher. At first blush the combination of the erotic French painting and the stodgy, congratulatory cantata texts is a difficult one to harmonize. Placing an alluring Venus in the lap of the august Professor of Jurisprudence at the University of Leipzig (the dedicatee of BWV 207) charges the atmosphere, certainly, but the charge is one that needs grounding. For Denis Grenier, the art historian whose essay accompanies the recording, the grounding is in a common spirit of gaiety and Bach's being "something of a bon vivant"; the grace and elegance of the Boucher painting, Grenier suggests, find an echo in the celebrative music of Bach.

Fittingly then, the performances are strongly marked with Leonhardt's elegant approach: tempos are often unhurried and leisurely voluptuous; the phrasing is highly contoured and frequently gestural-signature Leonhardt touches all, and much to be savored. The trumpeting by Emmanuel Alemany, René Maze, and Guy Ferber is something of an understated presence, impressively never challenging the overriding elegance, yet amply establishing the festal tone of the works.

Alemany, Maze, and Ferber are listed as playing trompettes naturelles sans trous (natural trumpets without vent holes). Listing them this way in the recording booklet seems reminiscent of recording marketing practices of the 1960s and 1970s, practices that proudly touted the use of "original instruments." The sound of period instruments eventually proved self-validating without the bold-faced labeling, but from a marketing standpoint, the ability to so label the recording gave it a competitive edge and helped buttress its claim to distinctiveness. Given the up-hill climb of historical performance at the time, one cannot begrudge the gesture, but today this taxonomic twist seems curiously antiquated and unnecessary. With the sole exception of the trumpets, every instrument is otherwise listed without qualifying description: violon, not violon baroque; contrebasse, not contrebasse baroque sans cordes faites de métal. Perhaps it is time that a trumpet is a trumpet, as well. One of the most impressive things about the trumpeting here is that, nomenclature aside, the players are so successful sans trous that one would not know that they are playing unaided by vent holes. The labeling seems to suggest that the means trump the ends, but in this case it is unnecessary pleading.

The quartet of solo singers is a uniformly accomplished one, though individually their strengths are diverse. English countertenor, Robin Blaze, sings with a remarkably free high range and notably fluid sense of line; tenor Markus Shäfer commands a wonderful purity of sound, while soprano Monika Frimmer is scintillating in tone and brilliant in manner, decidedly the most dramatic of the soloists; the Swiss bass Stephan MacLeod is notably agile and compellingly expressive, although there is a bit of flutter in the sound that may detract from time to time.

The secular cantatas open the door to Bach's propensity for musical recycling. For instance, much of "Angenehmes Wiederau," written in 1737 in salute to the political advancement of Johann Christian Hennicke, resurfaces liturgically in the next year as "Freue dich, erlöste Schar." "Vereinigte Zweitracht," written for the installation of Gottlieb Kortte as Professor at Leipzig in 1726 both borrows and lends: it memorably adapts music from the first Brandenburg concerto and years later resurfaces in large part as "Auf, schmetternde Töne," a Name Day offering to the Elector, August III. While expediency may have motivated a degree of the recycling, the recycling might also confirm Bach's pleasure in the music itself. It is a pleasure that we might easily share, especially in these elegant performances of Leonhardt and his forces.

-- Steven Plank, Oberlin College